For women and LGBTQ+, life in this pandemic-cursed year of 2020 was tougher than ever. The surging numbers of murdered women in Turkey has spiked even more, whilst parlimentarians discussed rescinding from the most important international agreement, known as the Istanbul Convention, that protects individuals against gender based violence. As the last of the municipalities won by the Peoples’ Democratic Party in the local elections of 31 March 2019 was run down by the AKP government by appointing a mayor and jailing the elected officials, the little hope of a political space was extinguished. While the majority of the Kurdish women’s movement, along with our elected MPs are in prison, every municipal service offered to women in these areas were defunded and discontinued by the appointed mayors, leaving many women in dire conditions. In the last quarter of the year, we also witnessed Turkey entering into a war alongside Azerbaijan, proving that it speaks the language of militarism and war the best.

On the one hand, social media became the only remaining public space, strengthening the political voice on these platforms, and on the other, social media battles and polarizations have taken too much precious time and determined the agenda of feminists. TERF arguments have increasingly crowded social media, finding itself allies and an intellectual framework spewing transphobia. However, we have also seen trans feminism gain a strong voice in opposition. As stories of abuse and harassment became public knowledge in the last days of this year, women in Turkey, especially women in literature and publishing have urged us to look at the score and mechanism of violence perpetrated by “intellectual” men of high regard. It has been quite a year! While we were floundering through this year, what have other women and queer around the world been going through?

The struggle put up by Polish women and LGBTQ+ for their basic human rights, filling streets and squares by the millions, and the Argentinian women hitting the streets to celebrate their recently gained right to abortion have both made the top headlines of 2020. We watched Mexican women set a courtroom on fire in the state of Sonora, as a response to the state’s inaction to the raging numbers of femicide. We also caught a glimpse of the discussions around Kamala Harris becoming the next Vice President of the United States, and if this is a feminist win or not. We wandered how Lebanese women and queer activists persevere, on top of an economic crisis and a political tempest in the midst of protests bursting throughout the country, and continue their fight after the horrid explosion of August 4. We also witnessed the terrifying events that unfolded upon the Citizenship Act put forth by the Modi government in India, and also the “greatest strike in the world” with 250 million workers marching through the streets.

As we near the end of this cursed year, as 5Harfliler, we wished to lend an ear to our fellow feminists across continents. We asked our friends in Mexico, Poland, South Africa, Brazil, Lebanon, Tanzania, Germany, Iran and India, how 2020 was for them. What was on the agenda of feminist and queer movements? When coupled with COVID-19, what did state violence, male violence, economic inequality and deprivation look like? How has the feminist movement mobilized? How has it generated solutions to the infrastructural problems exacerbated by a raging pandemic?

Although this is only a fraction of the map of our exhausted world, we hope that what has come together in this compilation will allow us to peer into 2021 with sharper eyes and senses, and figure out better ways to stand in solidarity with each other in a transnational and trans feminist future we wish to build. We hope that this summary account of various feminist and queer actions will give us new ideas about establishing political alliances, claiming our rightful place and weaving a feminist road map…

(For the Turkish version click here.)

Brazil – Bárbara Paes, Minas Programam

(many thanks to Ani Hao for the introduction)

I’m a Black feminist from Brazil with a Masters in Gender and Development. Back in 2015, I co-founded Minas Programam (which translates to “women coding”) with Ariane Cor and Fernanda Balbino. Minas Programam is a place for girls and women from São Paulo to learn about technology. When we first started, it was hard to find places to learn programming and to code that weren’t expensive or almost completely unwelcoming to girls and women and non-binary people, especially if you were from poor and underpriviledged neighboorhoods, if you were a racialized person, and if you couldn’t afford a pricey course. So, we wanted to create that space. At Minas Programam, we offer courses and classes to girls and women (mostly of color, from neighborhoods that are far from the city center). The classes are all free and taught by women and non-binary people.

Two issues come to mind thinking of the past year and the challenges that lie ahead: One is the racist violence against people of color and the other is related to sexual and reproductive health and rights. Brazil is a country that was built on structural racism and on the oppression of indigenous peoples and Black brazilians (brazilians of african descent). Every day, dozens of Black brazilians are killed by the police force, are deprived of quality health care, education, and job opportunities. (At the end of November, we’ve had manifestations around the country in protest of the brutal murder of a Black 60-year-old man).

At the same time, the current president is representative of a wave of extreme-right politicians who have been threatening women’s rights for a long time. I wrote this short article with a friend last year and I think it pretty much sums up my concerns. During COVID-19, all of the issues we address in the article got worse. As we wrote in the article, as soon as Bolsonaro came into power, the organs responsible for public policies for women were demoted and lost considerable funding, and the bills and constitutional amendments aiming to undermine women’s sexual and reproductive rights continue to be a challenge for women’s rights groups, and of course, violence against women and women’s access to abortion remain alarming issues. (Abortion is legal in some cases in Brazil, but only 55% of hospitals that used to perform abortions are still doing it at the moment).

Image: Tomaz Silva, Agência Brasil

There are so many groups working on these varied topics, I struggle to come up with a list! I really appreciate the work of organisations like AzMina and Instituto Anis, who are building a fund to support women to have access to safe abortions. Also, I’d like to mention Mulheres Negras Decidem (Black Women Decide), which has been mobilizing women all over the country to join politics. In a country with high rates of political violence against Black women and extremely low percentage of Black women in politics (even though 27% of our population are Black women), this work is really important. They’re a group of young Black women in Brazil who are organizing to have more Black women elected to political offices here in Brazil. Not sure how much you know about this, but while more than half of Brazil’s population is of african descent, the number of Black people occupying positions of political power is extremely low. So the work they’re doing to strengthen Black women who are running for office with progressive, anti-racist, anti-sexist agendas is really groundbreaking. I found this article which gives a bit more context in English. Also this one could be interesting. Something *really* cool they did was this whole in depth research where they interviewed activists from the whole country (which is saying a lot, because this country is huge) to understand where Black Brazilian women’s movements are heading. This type of research never existed before. Main learnings from the research show that these activists are already doing groundbreaking work (in many areas: supporting people/communities affected by COVID, rallying and protesting for their rights, creating solutions for social justice when the government doesn’t do enough). It also demonstrates that the solution for this crisis is not going to come from the same political powers who’ve always been in charge but from these activists and their determination to come up with solutions on the ground.

Another really cool example is the work done by Blogueiras Negras, they were one of the first online platforms dedicated to publishing Black Brazilian women. A place where women can publish their work, thoughts, discussions and reflections. Their work really spread Black feminism to wider audiences and generated public conversations about Black women’s various experiences. After almost 8 years of work, their platform is really a snapshot and a living archive of Black women’s activism in my country.

Feminism in Brazil has many different approaches. Considering Brazil’s history and current context, I personally believe feminism should strive to fight against the oppressions that different women face according to their different identities and societal structures. For me, that means that in order to be truly liberating and effective, feminism needs to look at gender, gender expression, race, ethnicity, disability, class, origin and many other things. For me, Black women’s activism in Brazil has been doing the most groundbreaking work! Because it recognizes differences, it recognizes how gender, race, class and other structures are operating simultaneously in our lives.

Hashem Hashem, campaigner, poet and performer from Lebanon

Despite the worldwide lockdowns brought on by COVID19 pandemic in 2020, Lebanon’s economic collapse, state crackdown on activists and the devastating Beirut port explosion on 4 August, feminist activists and groups in the country remained far from idle. The first few months of 2020 witnessed the mobilization of predominantly Ethiopian, Sri Lankan, Bangladeshi and Kenyan women migrant workers who protested for days in front of their embassies in Beirut demanding to be repatriated, after a wave of layoffs and abandonment by their financially struggling Lebanese employers. In addition to supporting the repatriation campaigns, local and international feminist and human rights groups in Lebanon such as the Anti Racism Movement (ARM), the Migrant Community Center, Amnesty International, KAFA, Legal Agenda and Human Rights Watch campaigned heavily to abolish the Kafala system, an inherently abusive migration sponsorship system, which ties the legal residency of the worker to the contractual relationship with the employer, placing them at higher risk of exploitation, forced labour and trafficking. As a result, the Lebanese Ministry of Labour instated a new standard unified contract as a reformative measure, but the contract was annulled in October by the Shura Council, the top administrative court, following a complaint by the owners of recruitment agencies in Lebanon. The fight continues to reinstate the unified contract as a first step towards the abolishment of the Kafala system.

Kenyan migrant women protesting in front of the consulate in Beirut.

In continuation of the uprising that erupted on 17 October 2019, feminist activists continued to be among the most politically organized and vocal groups on the streets, on social media, in labour and student unions and within independent political parties such as Lihaqqi which includes a highly active feminist committee. Moreover, independent and secular student groups that adopt radical feminist discourses achieved historic wins in the student elections at two of Lebanon’s top universities: American University of Beirut and Universite Saint Joseph.

As in many parts of the world, the rate of domestic violence in Lebanon spiked with the recurrent lockdowns, drastically increasing the volume of calls on the police hotline for domestic violence complaints. However, September saw the first “remote” protection order issued by a Lebanese judge over Zoom in favor of a woman survivor of domestic violence.

Throughout the year, women’s rights groups stepped up their demands campaigning for the reform of custody rights and other discriminatory personal status laws administered by religious courts in Lebanon. The campaign to end child marriage continued as well, albeit the parliament not passing the law yet. Furthermore, the public discussion about sexual harassment and justice progressed as collective lawsuits were filed against serial harasser Marwan Habib. This new wave of exposing, naming and shaming harassers and rapists has brought down some public figures such as the famous theatre maker Michel Jabre among other big names. It’s fair to say that the tides have turned

This “new” reality was reflected in the parliamentary session on 21 December, whereby the parliament criminalized sexual harassment after almost a decade of advocacy and campaigns by various feminist groups. Despite the loopholes, the new law is still considered a positive step. Moreover, the eventful session saw the parliament approve a few amendments of the Law on Protection of Women and Family Members from Domestic Violence (passed in April 2014), while rejecting other significant reform proposals and limiting legal protection to the “wife” only, thus excluding all other family members. In addition, the parliament furthered the discrimination against sex workers by increasing the prison sentence for “prostitution” from 1 year to 3 years.

Finally, perhaps one of the most refreshing developments of 2020 is the proliferation of new feminist or feminist-leaning platforms for knowledge production such as Hammam Radio, Akhbar Al-Saha news page and the 17 October newspaper.

Year 2020 was a tough lesson for humanity, but it also taught us that our communities will always be as tough and resilient as it takes to rise up to the occasion.

South Africa – Lindi Mkhumbane, activist, studies law and lives in Pretoria

For women, children and LGBTQ+ groups in South Africa, 2020 saw an intensification of previous struggles over land and housing, employment and opportunities, bodily safety and social security.

On 27 March, the South African government enforced one of the toughest lockdowns in the world: non-essential work and services were shut down, schools closed, the sale of alcohol and cigarettes was banned and a national stay-at-home order declared. From being further locked out of economic activity to being locked in doors with abusive intimate partners, the pandemic restrictions only sharpened the gendered nature of poverty and inequality. Women took on greater burdens and risks with their higher participation in paid and unpaid care work, precarious and unprotected informal work. Despite death rates being higher amongst men, it was estimated in June that more women (57%) were infected compared to men (42%).

Whilst keeping employment proved to be almost impossible for the majority, statistics released for the first quarter of the year revealed that women were disproportionately affected. Of the three million jobs lost, two million of those were women’s employment (with African women being the most affected). Where pitiful pandemic relief grants were provided, 65% were paid to men. The ripple effects were felt across households and communities, as a majority are headed by single mothers.

Prior to the pandemic, the official record was that one woman is killed every three hours; and this we know to be five times higher than the global average. More than 120,000 victims rang the national helpline for abused women and children in the first three weeks alone. This is more than double the usual volume of calls.

Though pandemic regulations put a halt to eviction orders, many women had to fight for their homes, as violent demolitions remained routine. Women of Abahlali baseMjondolo (a shack dwellers movement for land and dignity) said it best: “We are afraid of the coronavirus, but there is no virus worse than not having a place to stay.”

Sex workers were also on the receiving end, struggling to access inter alia contraceptives, and abortion services, putting the health of these women at even greater risk. The routine harassment of sex workers continues even when lockdown regulations are relaxed. On the weekend of 4 December, 57 sex workers were arrested throughout the country. No charges related to sex work were brought, but those who were undocumented were charged under the Immigration Act.

What has equally been a feature throughout the year is the resilient push back led by women, queer women and sex workers relentlessly demanding for dignity. Nurses and community health workers continue to demand for protective equipment and better support. Ordinary women continue to fight to keep their homes, to keep the fruit and vegetable stalls open to feed their children and continue to demand an end to the structural inequality we see manifest in the pay-gap, in the home and in social life.

Mexico – Dawn Marie Paley, journalist and author of Drug War Capitalism. She’s based in Puebla, Mexico.

Abortion rights and an end to violence were the key issues that brought women, queer and trans people and their supporters into the streets in Mexico this year. The International Women’s Day (IWD) marches were the largest on record, but the excitement and power on the streets in early March were soon blunted by the spread of Covid-19. As the pandemic took hold, collectives began organizing to deliver foodstuffs and goods, as well as monitoring violence as quarantine kept many families at home. By the fall, though the virus continued to spread and few had access to healthcare or government assistance, folks were back in the streets.

This year began with the tragic murder of artist and activist Isabel Cabanillas by gunshot in Ciudad Juarez, on the US-Mexico border. Cabanillas was part of the Hijas de su Maquilera Madre collective, whose members immediately mobilized following her murder. Women in Mexico City took in the streets in Februrary, following the murder of 25 year old Ingrid Escamilla and the circulation of images of her mutilated body, and the torture and killing of 7 year old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighet.

A mural for Isabel Cabanillas in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Photo- Dawn Marie Paley.

These initial, high profile murders came on the heels of a year in which nearly 4,000 women were murdered and 1,227 women were disappeared. Extreme forms of violence against women, often carried out by intimate partners, have surged as state and paramilitary violence –primarily enacted against men– has become widespread in the name fighting of the war on drugs.

On March 7th, friends and family of Cabanillas as well as hundreds who participated in social groups she was part of marched in Ciudad Juárez. Women first gathered to wheatpaste the photos and names of men accused of rape and harassment under a notorious underpass. Hijas de su Maquilera Madre called the march one day before IWD to show their disagreement and anger at institutional women’s groups, who have close relationships with the state and prosecutors and who tend to take more watered down political positions.

8 Mart 2020 Meksiko şehri, Fotoğraf: GALO CAÑAS /CUARTOSCURO.COM

On March 8, hundreds of thousands of women and allies flooded the streets in cities and towns across the country. An estimated 80,000 people marched in Mexico City. I was in Juárez, where local journalists said it was the biggest IWD march they’d seen.

“I see women in Mexico becoming more radicalized, in these past years we’ve seen that women are more organized, even here in the city, young women, women in high school and middle school are calling out aggressors in their schools, and that makes us very happy,” Sirena, an activist with Hijas de su Maquilera Madre, told me in an interview that afternoon.

The next day was a Monday, and some women responded to a call for a “day without women,” promoted initially by the trans-exclusive group Brujas del Mar and later by the Mexican government. A handful of corporations and state agencies gave women the day off. The action was confusing and de-politicized, failing to draw attention to the fact that Mexican women perform, on average, 5.5 hours of unpaid labor in the home every day.

Over the following weeks the COVID-19 pandemic became a reality in Mexico, and folks were asked to stay inside their homes, aggravating violence against women and sowing confusion and fear. The high spirits of March 8th were dampened as the fear of gathering spread. Even in this context, women in Guanajuato state were on the streets in May when their state congress discussed legalizing abortion, as happened in Veracruz in July. The legal abortion initiatives did not pass in either state, though abortion was decriminalized in Oaxaca state in September, making it the second jurisdiction in the country to do so after Mexico City.

In July, trans activist and medical doctor Elizabeth Montaño was killed in Morelos state. She was one of 45 trans people murdered in Mexico this year. Life expentancy for trans people in Mexico is a mere 35 years, and killings of trans people take place at one of the highest rates in the world. Queer and trans folks marched against violence in Mexico City in September.

Elizabeth Montaño

On September 2, two women whose children were victims of violence refused to leave the National Human Rights Commission’s (CNDH) office after a meeting with the head commissioner. They called for back-up and received the support of feminist collectives, two days later the occupation started in earnest. The women involved famously defaced and auctioned off a portrait of former president Francisco I. Madero. Solidarity actions took place in cities around the country, as women symbolically occupied state-level Human Rights offices; in Ecatepec, Mexico State, protestors were violently removed from the building.

Marches took place around the country on September 28, International Safe Abortion Day. In Mexico City, women were violently repressed and prevented by police from entering the city’s main plaza. The occupation of the CNDH continued, but internal divisions and trans-exclusive statements by some occupiers meant that by the end of October only a few dozen women remained (that number was down to a handful by December).

The murder of Bianca Alejandrina, who went by Alexis, in the tourist hotspot of Cancún brought hundreds of women into the streets again. Police fired live ammunition, hitting two protestors and injuring fifteen more, generating a national scandal.

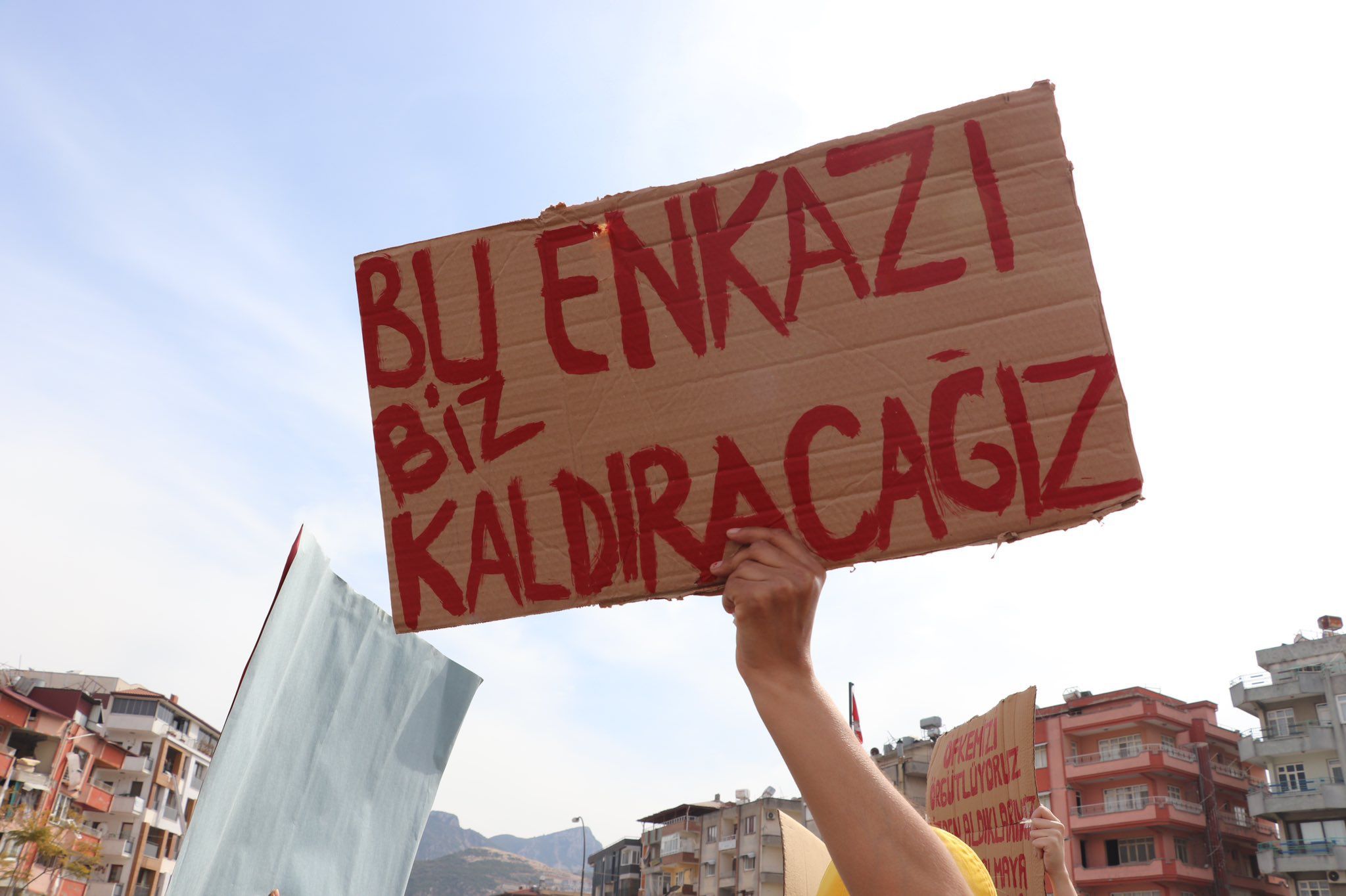

“There are so many murdered women around me, I don’t know where to cry.” March 7, 2020, Ciudad Juarez. Photo- Dawn Marie Paley.

On November 25th, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, feminist collectives and supporters throughout Mexico marched again. Increasingly, cities are deploying women police officers against women-led demonstrations. The mainstream media promotes debates about the use of “violence” by women. Social media reflects a widespread willingness by women to refuse to criminalize property damage and vandalism as violence, instead arguing authorities seem more concerned about walls and windows than about women’s lives.

On November 23, a group of women took over the state congress in Puebla. Central among their demands is safe, free and legal abortion, which has been debated multiple times, to no effect. As of mid-December the occupiers continue to hold the space, displaying the trans flag as a rejection of TERFism, an important gesture in a context in which many collectives are embracing trans-exclusive feminism.

Iran – Shahrzad Mojab, academic, activist and professor at the University of Toronto. Among her books are Marxism and Feminism (Zed Books); Violence in the Name of Honour: Theoretical and Political Challenges (Istanbul Bilgi University Press); Women, War, Violence, and Learning (Routledge)

Another Year of Suppression, 40+ Years of Resistance

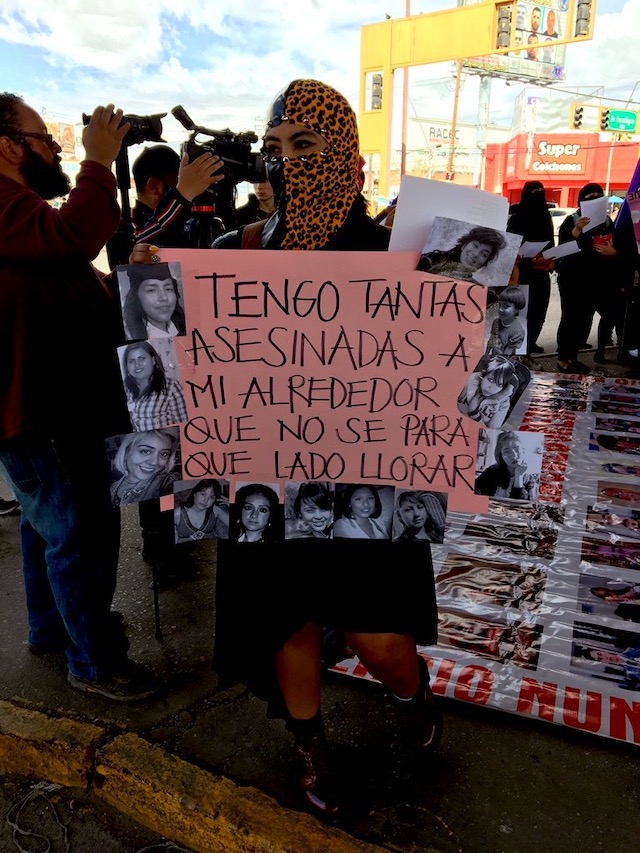

Women in Iran lived through waves of suppression, terror, imprisonment, torture, and execution by the Islamic regime in 2020. The state suppression, nonetheless, was confronted by waves of resistance and women’s struggle continued to target the totality of this regime. This new wave of resistance was rooted in the nationwide uprising of people in November 2019 against the Government’s decision to triple gasoline prices. The month of November 2019 since then is known as the Bloody November (آبان خونین) where series of nationwide civil and peaceful protests were brutally suppressed, the Government shut down the internet, killed 1500 of protesters, while has ruthlessly implemented a plan of non-stop arrest, imprisonment and torture. Iran Human Rights Group reports that between 2019-2020, 53 human rights activists have been arrested and have sentenced to in total of 400 years and 787 lashes. 2020 has not been an ‘exceptional’ year in the history of the Islamic Republic in suppressing women, journalists, activists, writers, students, and workers. In a recent report by Amnesty International called the “Blood-soaked Secrets” we read about the massacre of political prisoners throughout the 1980s; a continuity of violence without state impunity.

Women in Iran are living the consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic in an intensified manner. Poverty, hunger, domestic violence, suicide, and depression are few marks of the violence of the pandemic on women. Those inside the prison walls are also living through the horror of COVID-19 in addition to torture, interrogation, and solitary confinement. In October 2020, in a span of few weeks, the Government arrested many more women and union activists. Therefore, a major resistance initiative was launched called Burn the Cage Free the Birds: Free Political Prisoners in Iran. This campaign represents a 40+ years unceasing women’s struggle in Iran against the patriarchal theocracy and carceral capitalist regime. This campaign aspires to expand its reach beyond Iran and demand Free All Political Prisoners in the Middle East and North Africa. Women throughout the Middle East and North Africa should unit in creating a vigorous abolitionist movement in the region which extends beyond and over prison walls to demand the abolishment of the capitalist racist patriarchal structure which makes incarceration a routine state practice.

Let’s join forces and voices to cry out loud the names of political prisoners and demand their immediate release: Nahid Taghavi, Shabnam Ashouri, Loghman Pirkhezrayian, Neda Pirkhezrayian, Bahareh Soleimani, Somayeh Kargar, and Hanif Shadloo, and Nasrin Setoudeh among several hundreds more.

Germany – International Women’s Space (migrant women fighting patriarchy)

Overall, the feminist movement has responded well to the challenges of the past year. There have been several mobilizations around important elections, for the right to abortion, in support of the work of health professionals, which in Europe is occupied by many migrant women. There have also been countless solidarity campaigns warning of the dangers of isolation and the vulnerability of women exposed to a violent environment. Without a doubt, 2020 was a year in which the feminist movement showed its presence and power on the most diverse and important fronts.

2021, however, will be a year in which the feminist movement will have to be double aware because it is to be expected that in the name of ‘saving the economy’ women’s issues and agendas will be pushed into the background. For that not to happen, it is essential that the feminist movement recognizes that isolation for undocumented migrants, asylum seekers and refugees is a rule and not an exception caused by a pandemic. As feminists, we expect that, due to experience and hopefully massive understanding of what isolation means, our 2021 feminisms will be looking beyond the borders of citizenship and will add the demands of all migrant women to the list of challenges of a post pandemic world.

Christina Mfanga. Tanzania (Member of the Cooperative of Manzese Women Credit and Serving Association.)

While resisting exploitative systems, working class women in Tanzania are building alternatives. Working class women in Tanzania are no different from their counterparts around the world and especially ones in the third world countries. Living under imperialism, they are deprived of almost everything including basic social services they need so much, such as maternal health services. In Tanzania, women in the grassroots have been struggling on different fronts: Those in rural areas are leading in the struggles against land dispossession, invasion of the agribusiness companies like Monsanto and exploitative loans in the form of agricultural inputs. In the urban areas, their struggle is mainly around the exploitative financial institutions which loot their every sent through the loan system. Dispossession of land for some large infrastructure constructions, when coupled with poor constructions, cause havoc in the poor community settlements and make this another area of struggle for urban women.

Against the exploitative financial institutions, these brave women have been establishing their own savings and credit associations. These are democratic spaces run by them with everything generated in these associations divided equally. In rural areas, peasant women have been resisting the agribusiness by protecting their indigenous seeds and sharing knowledge on agroecology and other safe agricultural methods. They also resist land dispossession through legal actions and sometimes demonstrations and protests. Generally, women in the grassroots have been at the fore front of these actions and many other struggles against both patriarchy and imperialism in their various disguises. On this day, I call upon all the progressive forces to join the voices of women and especially the grassroots women who are faced with violence of all kinds in their daily lives and even in their struggles to liberate themselves. To my fellow women, nothing should stop us, not even the violence itself because it is for that reason and many others, that we must continue to fight for our dignity and the dignity of all.

Poland – Agata Kowalewska, artist and PhD student at the University of Warsaw

Julia Kata, Trans-Fuzja Vice President

Agata Kowalewska:

You will never walk alone! is the main motto of the 2020 wave of protests in Poland in the name of queer and women’s rights, which became the largest demonstrations in the country’s post-transformation history. The first half of the year was dominated by an increasingly hostile and dehumanizing anti-LGBT narrative from the ruling right-wing coalition and allied Catholic Church officials in a strategy to secure the second term for Andrzej Duda in this year’s presidential election (Duda famously said “LGBT is not people, it’s an ideology”, he won the presidency). Many municipalities and counties passed discriminatory legislation and advertised themselves as “LGBT-free zones.” This happened with the support of a growing network of anti-choice and anti-LGBT NGOs (most significantly, the Ordo Iuris Institute). Emboldened by the politicians and clerics, everyday homophobic violence increased drastically, which resulted in some queer people deciding they had to leave the country. Poland was ranked as the worst EU country for LGBTQ+ rights in the “2020 Rainbow Map” produced by ILGA-Europe. To counter the violence, protests and prides were organized, in some cities for the first time ever. The summer brought an escalation of state repressions, with police crackdowns on queer activists, most famously – Margot Szutowicz from the Stop Bzdurom (Stop the Bullshit) collective, a group of young queer anarchists raising sex-ed awareness and battling anti-abortion and homophobic misinformation spread by the anti-choice organizations, both online and through direct action.

Margot Szutowicz

She was arrested and spent three weeks in jail for damaging a truck covered in homophobic slogans and putting a rainbow flag into the hand of a statue of Jesus. Initially sentenced to two months, she was released earlier thanks to local and international pressure. This is an example of how social support of and interest in queer activism grew amidst increasing state violence. Around the same time, the Polish government initiated the process to revoke the Istanbul Convention, which they claimed was unnecessary and brought in “foreign values and gender ideology”.

As the COVID-19 cases soared and, like in other places, the consequences of the pandemic were hitting vulnerable people the hardest, on 22 October the government-appointed Constitutional Tribunal ruled that abortions for foetal abnormalities violated the country’s constitution. This decision effectively made almost all abortions illegal, as Poland had already had some of the strictest anti-abortion laws in the world. The reaction was immediate and thousands of people – mostly young women, queers, and their allies – took to the streets. Already on the first night of country-wide rallies the police used pepper spray. Despite that, the protests grew and were taking place almost daily, gathering wider support. Most importantly, they also spread to smaller towns and activated groups of people who had never participated in street protests before. The biggest protest night so far involved over 430 thousand people in 410 different locations throughout the country. Although largely leaderless, the protests focus around the Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet, a feminist movement that started in 2016. Various, mainly neoliberal politicians have been trying to piggy-back on the movement, but the response is always swift rejection, the more so if they are trying to instruct the protesters how they should be protesting, what goals are “realistic”, and how not to scare the “average people” off. Unapologetic, the movement also triggered mass apostasies, as more people felt the need to disassociate themselves from the overtly homophobic, misogynistic, pedophilia-hiding institution of the Polish Catholic Church.

The Polish society has been increasingly divided in the recent years over many issues, including the refugee crises, climate change and the environment, and LGBTQ+ rights. 2020 is important because it has seen people rally round against oppression. Young women on bicycles and older taxi drivers block the roads together; coal miners, farmers, EMTs, bus drivers, and teachers have shown their support. Many people are taking crash-courses in direct-action activism, learning how to deal with pepper-spray, how to stay together and avoid the police kettle. The protests also provide a platform for multigenerational solidarity – it is important to remember that between 1954 and 1993 abortion was legal in Poland. The movement created a precarious coalition. But, as the protests grow, sometimes some of the original messages of sisterhood, abortion on demand, and queer rights become overshadowed by a more general anti-government sentiment, which has been brewing for a long time. However, these messages of sisterhood (you will never walk alone!) remain at the very core of the movement, and queer activists continue to be at the forefront of the protests, including the Homokomando group, which was formed as a satirical response to conservative claims that LGBT militias were beating straight people up. Activist expertise and protection of fellow protesters became crucial (another one of our mottos is: when the state does not protect me, I will defend my sister – it rhymes in Polish), as police tactics turned increasingly brutal, including breaking people’s arms, beating protesters up, and sexually harassing them. But police brutality only resulted in galvanising the solidarity among protesters and summoning the help from people who had not participated directly, but were now opening their buildings’ gates to provide shelter to protesters escaping police arrests, offering tea (it is getting really cold in Poland right now!), or even just waving from their windows. Others volunteer their time as medical support for the rallies, pro bono legal aid, and financially support the protests and funds established for the victims of repressions (e.g. the Szpila collective).

Stop Bzdurom & The Anarchist Federation

Aborcyjny Dream Team, a grassroots organization that has been instrumental in helping thousands of Polish women to have safe abortions in the recent years, collected nearly PLN 1.5 million (over 400K US dollars) in just over a month. For every person detained by the police, there is a solidarity demo in front of the police station until they are released, even when the detainee is moved to a different town. Popular support for the women’s strikes grew up to 70% since the rise in state violence. This is despite the protests breaking with ideas of appropriate feminine behavior still prevalent in Poland. The protesters mobilize their rage, our battle cry is “wypierdalać” (it means fuck off, but more to the point). The movement stopped being just about the Tribunal’s ruling long ago – we are now marching for freedom, we are marching for everything. And none of us will ever walk alone!

Social media links to follow: @ogolnopolskistrajkkobiet @aborcyjnydreamteam @kolektywszpila @homokomando @stopbzdurom.pamietamy and @stopbzdurom

Julia Kata, Trans-Fuzja

Due to the dramatic situation with human rights in Poland, which escalated over the last few years with the prelude in the last quarter of 2020 (the judgment of the so-called Constitutional Tribunal on legal access to abortion), it shows that the next year, 2021, will be one of the most difficult in history.In the fight for access to abortion, the issues of its accessibility for transgender, non-binary and intersex people and their general SHRH are beginning to notice.Nevertheless, the TERF (trans exclusionary radical feminists) narrative has started to appear in the mainstream media and this is an issue that will require special attention.The year 2021 will require uniting and supporting each other in a common fight for equality and equal rights for many social groups

India – Japleen Pasricha (Founding editor of Feminism in India) & Meenakshi Thirukode (founder of School of Instituting Otherwise)

Meenakshi Thirukode:

I’ve been building a project that is looking at what radical study/radical education within a feminist praxis can mean in the current political environment. I run what is called the School of Instituting Otherwise – and at the moment we read, study, discuss and think about a ‘being together otherwise’. I think education is the most important tool to create a space for a radical subjecthood to emerge in current times. I’m living the life of a ‘feminist killjoy’ so to speak!

As everyone knows, currently, we are fighting a fascist far right government and an increase in ‘intolerance’ on the basis of religion, gender, caste. In this vision of a ‘Hindutva’ nation – there were protests that had been taking place since Dec 2019, against the Citizenship Amendment Act – a protest that saw huge mobilizations among the younger generation – a generation that was dismissed as being apathetic to politics. Since the pandemic, the State has weaponised the current health crisis to jail many of those same young activists and older activists for their stand against discrimination, murder and lynching on the basis of religion and caste – for having raised their voices against fascist forces who target dalits, transfolk, women, muslims… Currently the country is a police state, going through levels of intolerance that are deeply disturbing – for instance recently right wing trolls aided by a female Bollywood actress who calls herself a ‘feminist’ and is supposedly an advocate for mental health – trolled and bullied a gen z bahujan queer artist and anti-caste activist. Prior to the resistance movement, India had its wave of the #metoo movement as well – from LOSHA, which called out sexual harassment in academia initiated by a dalit student, to an anonymous instagram account that called out art world predatory behavior.

Pinjra Tod is an important collective of young women across universities in India that have been raising their voices against both the oppressive institutional system that has a bearing on their freedom of movement, expression and agency as women. It started particularly with strict dormitory rules for women, but the collective became a key voice within the recent resistance movement that took place, that saw many young people protesting for the first time – against the draconian ‘Citizenship Amendment Act’.

Pinjra Tod

Also, important to mention when speaking of feminism in India is that India, is a society organized through caste – a system of hierarchies of a social order that has led to the continued discrimination, erasure and genocide of Dalit, Bahujan communities as well as Adivasi and Tribal communities. Not to mention the violence encountered by transfolk as well. Often times Upper Caste/ Suvarna feminists appropriate, erase or co-opt the work of Dalit, Bahujan feminists and trans activists. So it’s important to mention a few important voices here including – Grace Banu, Vikramaditya Sahai, Priyanka Paul, Rajni Tilak, Jyotsna Siddhant, Yashica Dutt, Damni Kain, Kiruba Munusamy, Sumeet Samos, Manisha Maashal to mention a few with strong social media presences.

Japleen Pasricha:

The COVID-19 pandemic and strict lockdown in India have affected reproductive services such as maternal health, family planning, and abortion services adversely. While medical facilities and retail chemists were exempted from the lockdown, the curbs on movement, as well as enhanced fear of infection among patients and health providers, resulted in low availability of services. So, while the Government of India deemed RMNCAH+N (Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health and Nutrition) services as essential in mid-April, access and availability continued, and continues, to be a big challenge.

Women’s access to safe and confidential abortion services is a challenge even under regular, non-pandemic circumstances, with unsafe abortion still being among the top leading causes of maternal mortality in India. In the current public health emergency situation where almost, all public facilities have been repurposed to have a COVID-19 management focus, there are very few facilities that are providing abortion services.

This situation has led to a prevailing feeling that gains made in the country to address preventable maternal, newborn, and child mortality and morbidity in the last two decades will be reversed by COVID-19. According to estimates by health experts, millions of couples have lost access to family planning services, and there is an anticipation of an increase in unintended pregnancies, child births, and maternal deaths. There is likely to be an increase in unplanned and unwanted pregnancies at present due to a variety of reasons—lack of access to contraception, people being stuck at home for days on end resulting in not only a higher frequency of sex, but also increased rates of intimate partner violence and rape.

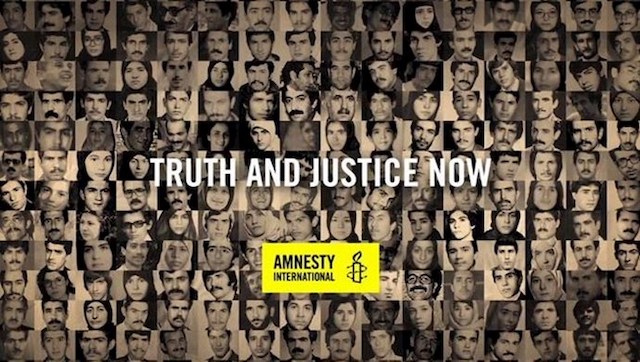

Image: 29 September 2020 Mexico protests.