Towards the end of the novella İstasyon (Metis 2020) by Birgül Oğuz, the protagonist Deniz looks at an illustration of a beach cabin drawn by her niece Elif who had been staying with her. She examines it carefully, turning the image to the side, and upside down, but still cannot tell whether footsteps drawn in the snow lead towards the cabin in the painting, or away from them. This quiet inscrutability, the serene silence of an artists’ motivations, makes her break down and cry.

We as readers are given just such an opportunity to sit with ambiguity throughout the novella. We can feel the care Oğuz has given to carefully finding a lightly tread pathway through her story, avoiding any excess facts or details. So much is left unsaid. In an interview with Nilüfer Kuyaş for the Kıraathane podcast (April 6 ), Oğuz admits to making the setting of İstasyon intentionally vague. Responding to Kuyaş’s comment that the story seems to have an attitude of “not wanting to give itself away,” (ele vermek) she affirms:

I didn’t want the story to signal to anything else besides its own spirit. Like, what time period, where, which country it takes place in…I didn’t want any of that to be front of mind.

(Hikâyenin kendi ruhundan başka bir şeyi işaret etmemesini çok istedim. Yani, hangi dönemde nerede hangi ülkede geçiyor… Bunlar önplana çıksın istemedim.)

Even though the story takes place on a small island located off the coast of a major city—which in most cases would be a dead ringer for Büyükada—the city is specifically referred to as “the capital” throughout the story almost as a way of assuring to readers that the city in question could not possibly be either Istanbul or Ankara. But any attempt at orienteering would be misguided. The spirit of the novel is mood not circumstance, place not geography. Without the need to know where she has come from and where she will go, we follow Deniz as she takes us with her on her long walks, wandering the landscapes of the island on small trails, through the forest and down the beach.

Oğuz is in good company as a Turkish author escaping to a speculative Island to avoid the burden of allegory and contemporary politics. The effort that both Pamuk and Oğuz have in explaining that their islands are not necessarily perfect stand-ins for Turkey is not due to faults of imagination or writing skill. It has everything to do with the suffocating, zero-sum cultural politics on the domestic front, and the restrictive, national-allegory framing forced on much of global literature on the international front. We should celebrate Pamuk’s Minger Island as it joins the ranks of countless other fictional geographies, those like Moore’s Utopia, Stephenson’s Treasure Island, Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, and T. Hardy’s Wessex, as Bengü Vahapoğlu put it in a recent tweet. These types of fictional geographies are meant precisely as a way of giving breathing room for contemplation, a healthy dose of cognitive estrangement for thinking through the circumstances of the worlds we live in, without the immediate need for them to correspond to historical and political facts. The ambiguity is the point.

Likewise, Oğuz’s İstasyon is precisely about learning to love and to respect others even when they are inscrutable. This goes for people themselves as much as their art. That is to say, how should we care for others without requiring them to explain themselves? How do we give others space and not ask them to ‘give themselves away’? This is not just physical space, but mental and emotional space as well. Deniz comes to house sit for her friend Nihal on the island in order to get some alone time, but even from far away Nihal sends a string of e-mails to check in. Although they clearly come from a place of attentiveness and concern, they annoy Deniz. When she doesn’t immediately respond, Nihal asks another woman, Bahar, to come check on Deniz in person. Bahar understands the imposition, and tells Deniz as much.

“You feel like you’re being inspected. And you’re right to”

(“Denetleniyormuş gibi hissediyorsun. Haklısın da.”)

The residents of the island all seem to have noticed Deniz walking around, and one even castigates her for being too lost in thought. Deniz doesn’t need to be checked on, she needs to be cared about enough to be left alone.

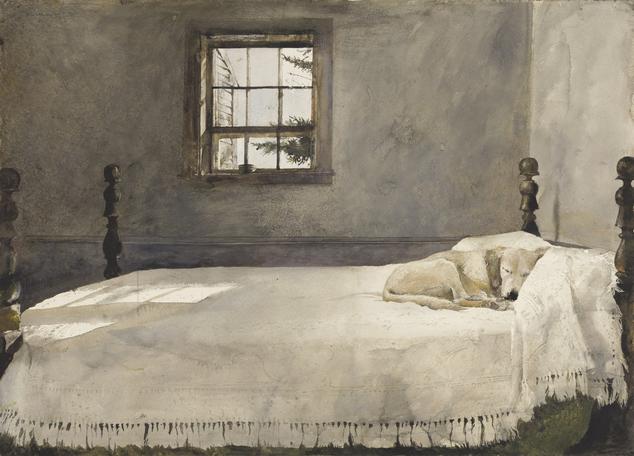

For her part, Deniz tries her best to exist alongside others, to care for them even, without asking them to answer to her. Elif comes to stay with her, and the child is almost totally silent, constantly looks at her phone, and Deniz struggles through the novel to find a way to relate to her. But nonetheless, Deniz’s actions show that she understands the dignity of not having to explain oneself, and that some of the most perceptive and attentive care is often silent. Deniz has this same approach with non-human others as well. She befriends a local dog named Arkadaş, who begins to accompany her on her long walks around the island, and who will even come in to sleep by the fire. But Deniz also lets Arkadaş come and go as she pleases, often leaving to go sleep in her own spot outside. The quiet dignity that Deniz grants to the dog is one of the most affecting elements of the novella.

At a pivotal moment of confrontation between Deniz and her niece Elif, Arkadaş awkwardly comes and stands in between them. It isn’t clear what she is doing or what she wants. The narrative focuses specifically on Deniz as she tries to decide how to react to this sudden change in the dog’s temperament at such an inopportune moment. She vacillates between anger and affection, and eventually decides to just let Arkadaş stand there. She puts care in thinking about how to react to the inexplicable behavior of another, and realizes the best thing to do is let the dog be in her strangeness. This decision suddenly gives Deniz a moment of profound emotional release, as though the dog’s behavior offers a key to unlocking her own emotional inscrutability.

The ethics of care in this novella are deeply moving. They are also universal, or at least universally feminist. It is a story about the subtle moral stances one takes in interpersonal relationships, the characters navigating between dependence and interdependence on one another. Nothing about the people or their relationships in this book necessitated the story be set in Turkey. As an American reader, I would have no trouble imagining the story taking place in a fictionalized Puget Sound, or the Outer Banks, or even Galveston Island. We too have nosy neighbors, taciturn pre-teens, and women looking for the freedom to be left alone.

That is, however, except for one detail. There is one relationship of care in the novella that was decidedly Turkish, and it repeatedly snapped me back from the universal to the specific and from the speculative to the anecdotal: the way humans relate to Arkadaş. As I have written elsewhere, “Whereas Americans treat dogs like their own pampered, unconditionally loving children, a Turkish person can see a dog in the street, living independently in the liminal space between nature and domesticity and help them without the urge to become their exclusive owner.” Were İstasyon to have taken place in Yoknapatawpha county, for example, there would have been a moral panic about wild dogs on NextDoor. Arkadaş would have been sent to a shelter and adopted long before Deniz ever arrived at the island. It would have been impossible for Deniz, as an American, to bring herself to grant Arkadaş the autonomy of her own behavior. Whether dragging them onto flights or putting them into baby strollers, projecting neuroses onto our pets is a national pastime. We have a lot to learn on how to let dogs be themselves.

But this difference reminded me that speculative islands like Oğuz and Pamuk’s, and fictional geographies in general, are not meant to be anonymous and generic. They are meant to be uncanny and déjà vu. More than anything they provide plausible deniability. All of the ethnic and international politics of late Ottoman society are still taking place on Minger Island. Likewise, the sense of crisis-ordinariness and ever-present threat of violence against women which plague Turkey seem to lurk just off shore from Deniz on her island. This is the backstory we can infer while reading, but not the one we must. We are free as well to just focus on just as much as what Deniz tells us.

This is all the more reason why İstasyon should be treated with the dignity of a universal work of global fiction rather than a representative of the Turkish ethos. Readers from other countries should be granted the opportunity to read such a beautiful work of literature that simultaneously presents such a moral argument for care based on accepting others’, even non-human others, in their ambiguity. The book has much more to say when it isn’t having to explain itself.

*You can read the Turkish translation of the review here.

Kapak görseli: “Master Bedroom,” Andrew Wyeth, 1965.